FLASHBACKS

Balmoral Room

MARK WEBB

When thinking about how to address the complex political, social and aesthetic implications of Chris Howlett’s exhibitions, I had something of a flashback of my own and was drawn to revisit Andrew Feenberg’s Critical Theory of Technology (1991). As I recalled, this was one of the first books I had read that specifically engaged capitalist, socialist, economic and cultural viewpoints in order to hypothesise on the role and functions of technology in our near future. In what turned out to be a key text on the subject, Feenberg provided an ambitious and challenging scenario for developing a democratically driven, and politically responsible approach to how advanced technologies like computing might be harnessed for egalitarian purposes. I was curious to see how Feenberg’s ambitions from nearly two decades ago might have manifested themselves in Howlett’s own explorations into the complicated interface between technology, art, and social and political practices in the early 21st Century.

Feenberg believed technology to be the defining issue of modernity. As a major component of contemporary society it was intimately connected to politics, economics, culture, to all aspects of social and personal life. And although he argued that the processes of labour, science and technology were constituted as forms of domination to both nature and human beings, he advocated that these processes could be democratically transformed as part of a broader program of radical social transformation.

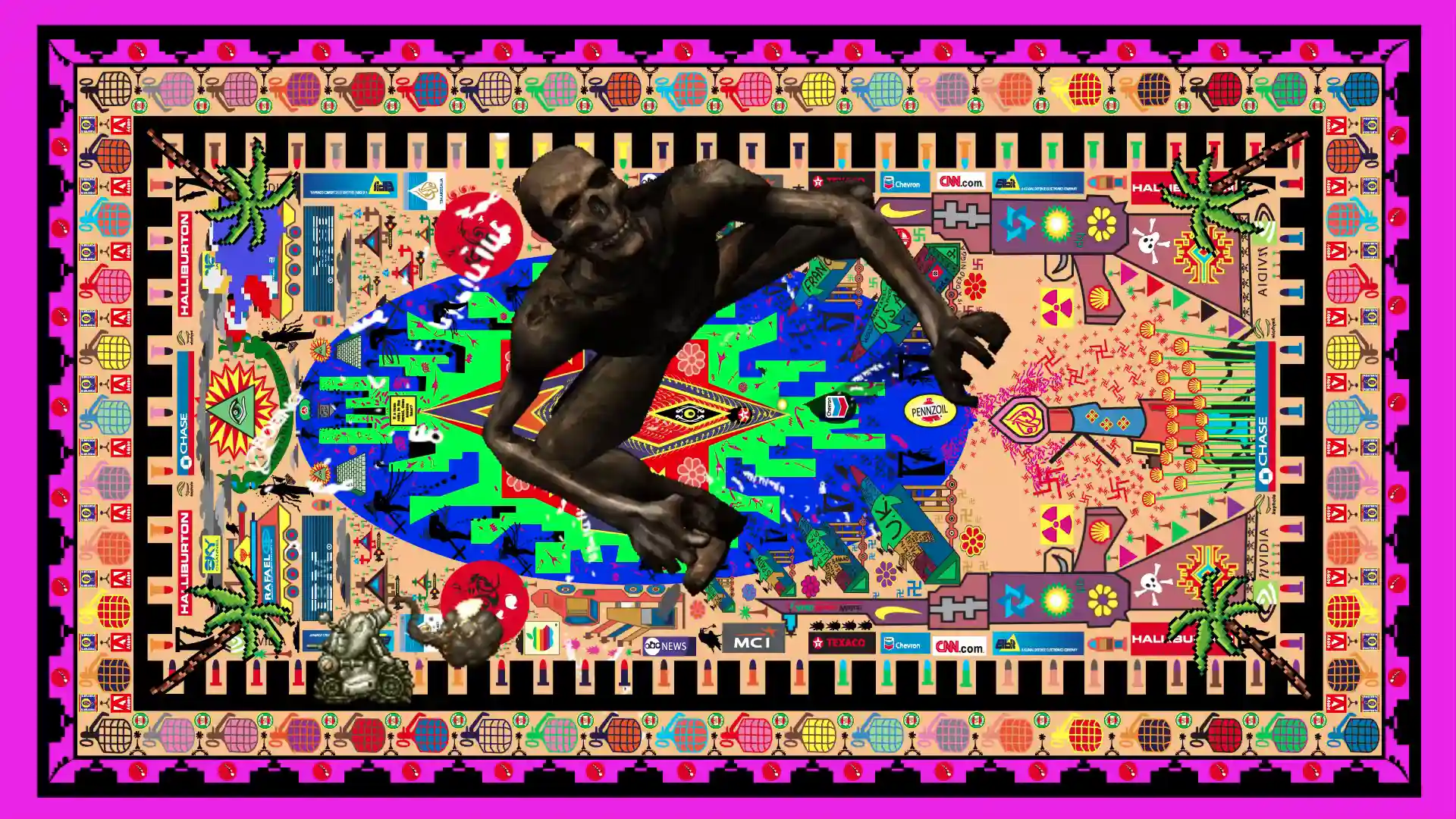

above: Flashbacks, 2009. Install detail. City Hall, Balmoral Room, Brisbane, Australia. Photography Brock Yates.

To achieve this goal of a more democratic and egalitarian society he argued against the prevailing opinions of the time that either slavishly celebrated technology’s modernising features, or blamed it for the crisis of Western civilization.

Feenberg argued for a rethinking of these simple binaries, to demonstrate how technology can be part of a process of societal democratisation. He believed that there could be no genuinely democratic and progressive political change without the reconstruction of technology, and, vice-versa, no radical change of technology without democratic political change.

In making his case for change Feenberg also identified how post-industrial technologies had so dramatically redefined fundamental social and economic relations that it affected the way that notions of identity and subjectivity were considered. In doing this he invoked the social historian Christopher Lasch’s notion of ‘cultural narcissism’ to discuss how these concepts of self become equally redefined. Lasch argued that since the beginnings of the 20th century in the west, there has been a collapse of public and family life, a gradual diminution of traditional relationships in communities along with an increase in the atomisation of the individual. This in turn led to a culture of competitive individualism, and to the “intensified pursuit of personal pleasure by individuals who have less identity than ever before.”

above: Flashbacks, 2009. Install detail. Michael Jacksons 4 Ways, Metropolis: Part I-III, Bushstalkers, City Hall, Balmoral Room, Brisbane, Australia. Photography Brock Yates.

Lasch further claimed that this new narcissism, thoroughly mediated via everyday technologies, established the conditions for the creation of artificial, invented communities in which the “individual becomes a discontented spectator on his or her own life, engaged in strategies of manipulation and control directed toward the self and others alike.”

Feenberg added his own observations about this redefinition of identity, “The computerisation of the human self-image places the subject now in the position of programmed device, now in the position of programmer.”. Written over two decades ago, these observations from Lasch and Feenberg appear eerily prescient when it comes to viewing how Chris Howlett utilises the ubiquitous technologies of everyday life to reflect on their role in shaping our social, political and cultural lives.

Certainly the potential of the Internet to open up new potentials for political and social discourse would seem to part of the ‘reconstruction and democratisation of technology ‘that Feenberg hoped for. However on another level, the unprecedented reach of technological connectedness that on-line life and instant communication delivers into all aspects of social, family and work environments has also further reconfigured the boundaries between those relationships. The pressure is on to be available 24/7, to be constantly connected, to not be outside of the loop. Work becomes play becomes work, private and public lives become conflated and confused into a complex array of real and virtual spaces. Yet our desire for even more advanced levels of connectivity to the noise of the world appears unabated.

This largely uncritical yet enthusiastic use of personal technologies surreptitiously ‘programs’ our lives. It maintains the illusion of being constantly ‘connected’, yet further distracts us towards isolation within our own individual pursuits, ‘twittering’ away at our own navels. And although certain social networking communities have also proven to have the potent political and social value that Feenberg had advocated, these appear heavily outnumbered by those that tend to simply reinforce our narcissist instincts and materialistic desires. The most popular sites like Facebook or MySpace provide the perfect location for the ‘discontented spectator’ to manipulate and control their social relationships, to ramp up the level of competitive individualism toward the acquisition of ‘friends’, and the sharing of their latest purchases. And then there are the issues around privacy and data mining that are inherent to these social networks, issues that we are apparently at ease with, or blissfully oblivious to, whenever we log on.

above: Flashbacks, 2009. Install detail. Bushstalkers (game-mod), City Hall, Balmoral Room, Brisbane, Australia. Photography Brock Yates.

It is little wonder that these narratives of the technological self have become so embedded into our ‘programming’ that we in turn reproduce these strategies of manipulation and control into ‘artificial and invented’ environments like the Sims. This hugely successful gaming franchise, which is part of many early childhood learning programs, totally relies on ‘the narcissistic instinct in the player’ to successfully gain adulation and fame in their virtual kingdoms.

These games, even more so than the massive virtual killing fields of World of Warcraft, Halo and Doom, are premised on ‘remodelling the world and are the expression of a solipsistic mind, of an I/eye that considers itself the sole source of reality, they are about playing God’. It is this ‘interactive scopophilic exercise’, a virtual extension of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon that allows the player ‘to gaze upon but not be gazed at’, and to ‘manipulate without being manipulated’3. that makes the Sims the ideal site for Howlett to investigate how technology and democracy might come together to simulate real relations of power and control.

Through combining 3D game play with interactive game mods, video projections, sound works and site-specific installations, Howlett explores how these technologies reflect where we might be now, as subjects, ‘in the position of programmed device…in the position of programmer’. His practice over the last decade or so has been exploring what Foucault calls the enunciative function in society.

This very generally refers to the way in which meaning is derived from a multiplicity of places, spaces and texts. More specifically it refers to the complex interrelationships and discursive practices that help to constitute what distinguishes the meaningful from the meaningless, and ultimately who it is that actually speaks to, and for us. This new body of work extends Howlett’s interest in how relative networks of power affect the possibility for the communication of information and the dissemination of knowledge. He does this through exploring the way in which these new technologies continue to shift social, political and cultural understandings of our physical and psychological selves.

The works in Flashbacks are designed to activate an immersive space from which to critically and creatively consider how reality and simulated environments both construct and reconfigure our ideas about the nature of subjectivity and identity. They ask us to reflect on how we function as a society in response to these new spaces of interaction. They challenge us to respond to the political dimensions of these expanded sites of inhabitation, and how they might also represent a more troubling scenario for the possibility of dissent or opposition in our media saturated culture.

above: Flashbacks, 2009. Install detail. Metropolis: Part I-III 2009-10, 1-channel, High Definition Video, PAL, Surround Sound. Ed of 5 +2 AP, 24:20 mins, City Hall, Balmoral Room, Brisbane, Australia. Photography Brock Yates.

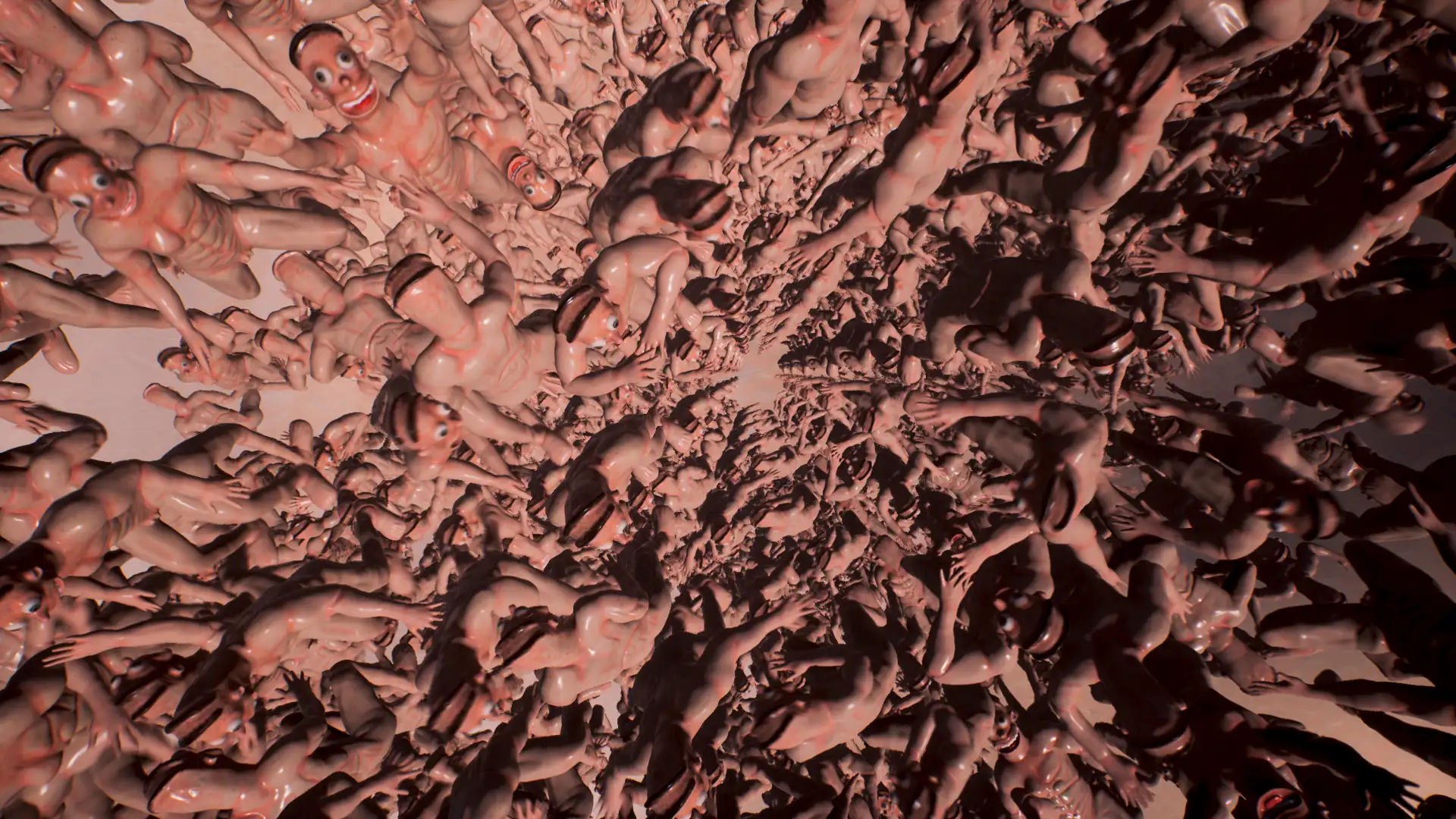

The three channel video work called Metropolis I, II, and III utilises the 3D video game called SimCity Societies to construct three imaginary zones. In these zones, three different societies have been constructed in order to challenge the logic of the game, and to generate certain narratives or psychological zones that in turn lead the audience to question their own perceptions about public and personal realities. These narratives, which are mapped across Howlett’s simulated environments, have been collected from the plethora of competing stories that incessantly stream across our networked culture. Some of these include online tributes from Michael Jackson fans, Iraq war veterans, peace activists, criminal confessions and first person shooter game storylines.

In the other body of work in Flashbacks called Frequencies, Howlett has reconfigured, or hardware hacked, iPod FM Transmitters to modify their capacity to receive and transmit information. Like the video and game works, this sound work also calls into play the logic of technology as it was designed, and extends his exploration into the construction and dissemination of meaning.

However rather than call attention to the truth or otherwise of the symbolic representations presented in Metropolis I, II, and III, Howlett carefully extracts fragments of “speech”, specifically the vocalised expressions that include moans, screams, grunts, groans, laughter, sighs, and silent gaps between words, in order to examine how these elements become part of the abstract structures of communication.

By transmitting these as radio waves to the array of radio receivers in the installation, these formless fragments construct machines for glossolalia that displace and disrupt the familiar narratives of the airwaves. What is encountered instead is a soundtrack of transitory and sensuous grains of the voice, at once referencing the textures, timbres and affects of the corporeal, but at the same time highlighting the liminal nature of their origins.

Alongside Flashbacks, the work in Frequencies establishes another site for reconsidering the transformative potential of digital media, but one that emphasises its poetic possibilities rather than it’s social or political dimensions.

This work also points to how the ongoing redeployment of technology in Chris Howlett’s practice develops a range of dialogues across the conceptual and material processes he examines. And that is what will be further explored in the next installation of Flashbacks at Metro Arts in September 2009.

Mark Webb

REFERENCES

- Feenberg, A. Critical Theory of Technology. New York, Oxford University Press. 1991 pp. 140-143.

- ibid. pp. 97-98. 3. Bittanti, M. All too urban: to live or Die in SimCity. in Atkins and Krzywinska eds. Videogame, Player, Text Manchester, Manchester University Press. 2007.

Special thanks to Mark Webb for writing the essay, Brock Yates for documenting the exhibition, MAAP for their generous loan of their audio-visual equipment and the support from two Brisbane artist run spaces Boxcopy and Accidentally Annie Street Space (AASS).