SEDUCTION IS IMPORTANT:

Chris Howlett'S wEAPONS ON THE WALL

CHRIS HANDRAN

Art is not a mirror to reflect reality, but a hammer with which to shape it.

– Bertoldt Brecht2

The title of Chris Howlett’s ongoing series of exhibitions comes from the description of World War II propaganda posters as Weapons on the Wall 3. This phrase indicates the extent to which such wars are not just about fighting an enemy, but also about waging a war for people’s hearts and minds. Support for a cause cannot be assumed, but must be won – through reason, inspiration, emotion and, if necessary, deception. Seen in this light, propaganda can be seen as advertising for an ideology; a very particular type of hype, designed to ‘work on people until they are addicted to us’4. Today, the tactics of propaganda are so deeply imbedded within the fabric of our culture that they are indistinguishable across the fields of media reporting, advertising, cinema or reality television.

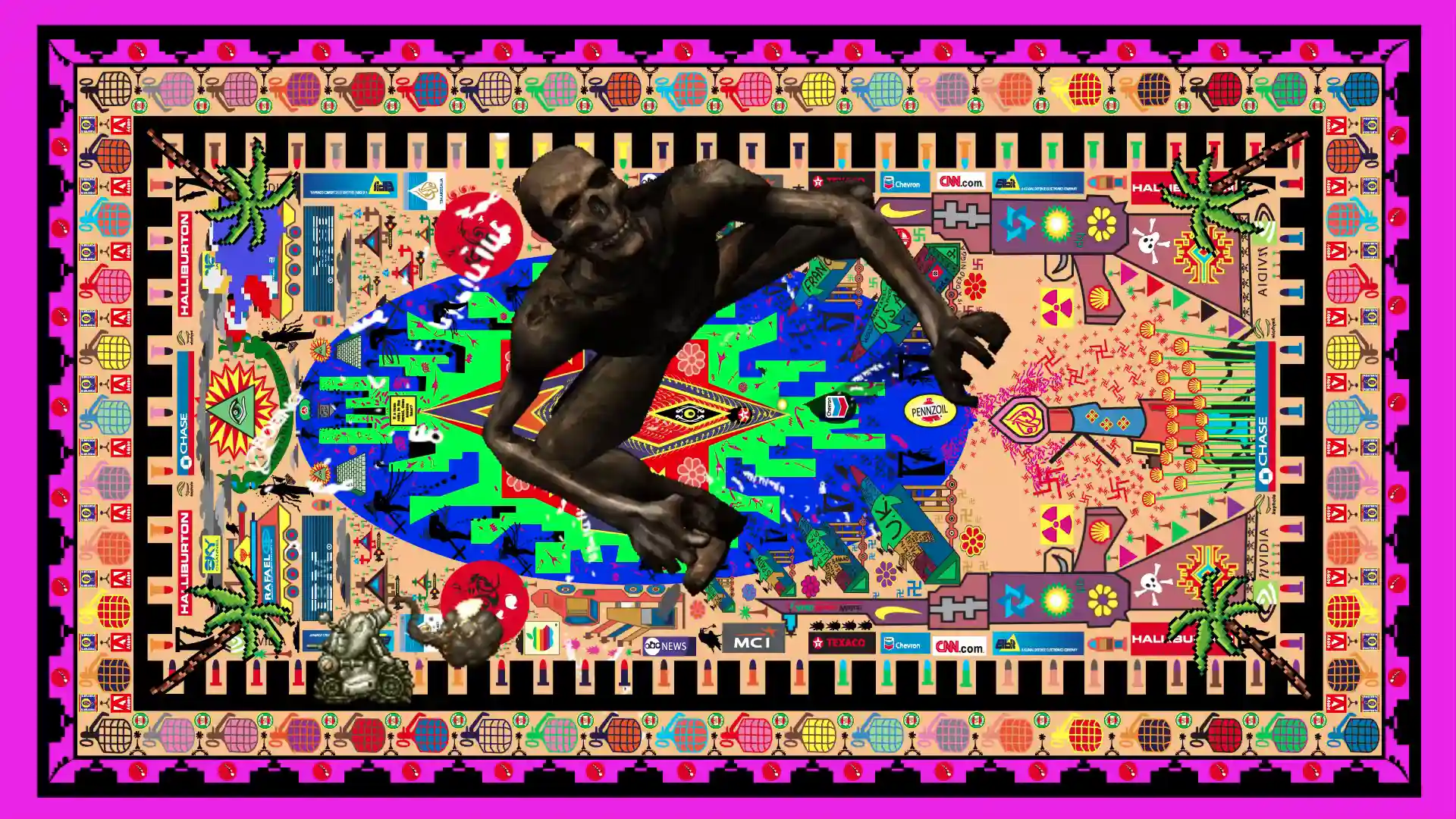

left: Weapons on the Wall, 2004-05. Installation details. Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane. Photography Richard Stringer. right: Weapons on the Wall: Bart Simpson toy doll, 2004-05. Detail. Yellow acrylic on plastic. Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane. Photography Richard Stringer.

It is in this context that Chris Howlett attempts to explore the relationships between art. politics and propaganda. The earlier editions of Weapons on the Wall drew heavily on representations and reporting of September 11, the US invasion of Iraq and the resulting protests against US Imperialism. They presented an eclectic array of hand-drawn protest placards, digital prints, paintings of magazine covers ranging from TIME Magazine to Art in America and videos including news reports from the ‘ground zero’ of September 11, the cartoon violence of the Simpsons. episodes of M*A*S*H and imagery from internet hate sites. These seemingly radical juxtapositions point to a certain equivalence amongst these varying statements: whether protesting against war or waging it. spearheading an advertising campaign or a terrorist strike. reporting on world politics or on contemporary art, all seems to come down to sloganeering and spectacle.

The most recent addition to the Weapons on the Wall project brings these investigations closer to home. examining the legacies of colonialism and nationalism within a local context, alongside the media critiques and political Interrogations of the earlier exhibitions. An important aspect of this protect is an acknowledgement of the complexity that is inherent in the issues under examination. In Howlett’s engagement with politics the idealism of Brecht’s statement is undercut by the awareness that there are no simple answers to the questions being posed, only a never-ending series of linked ideologies, oppositional arguments and conspiratorial connections to be explored.

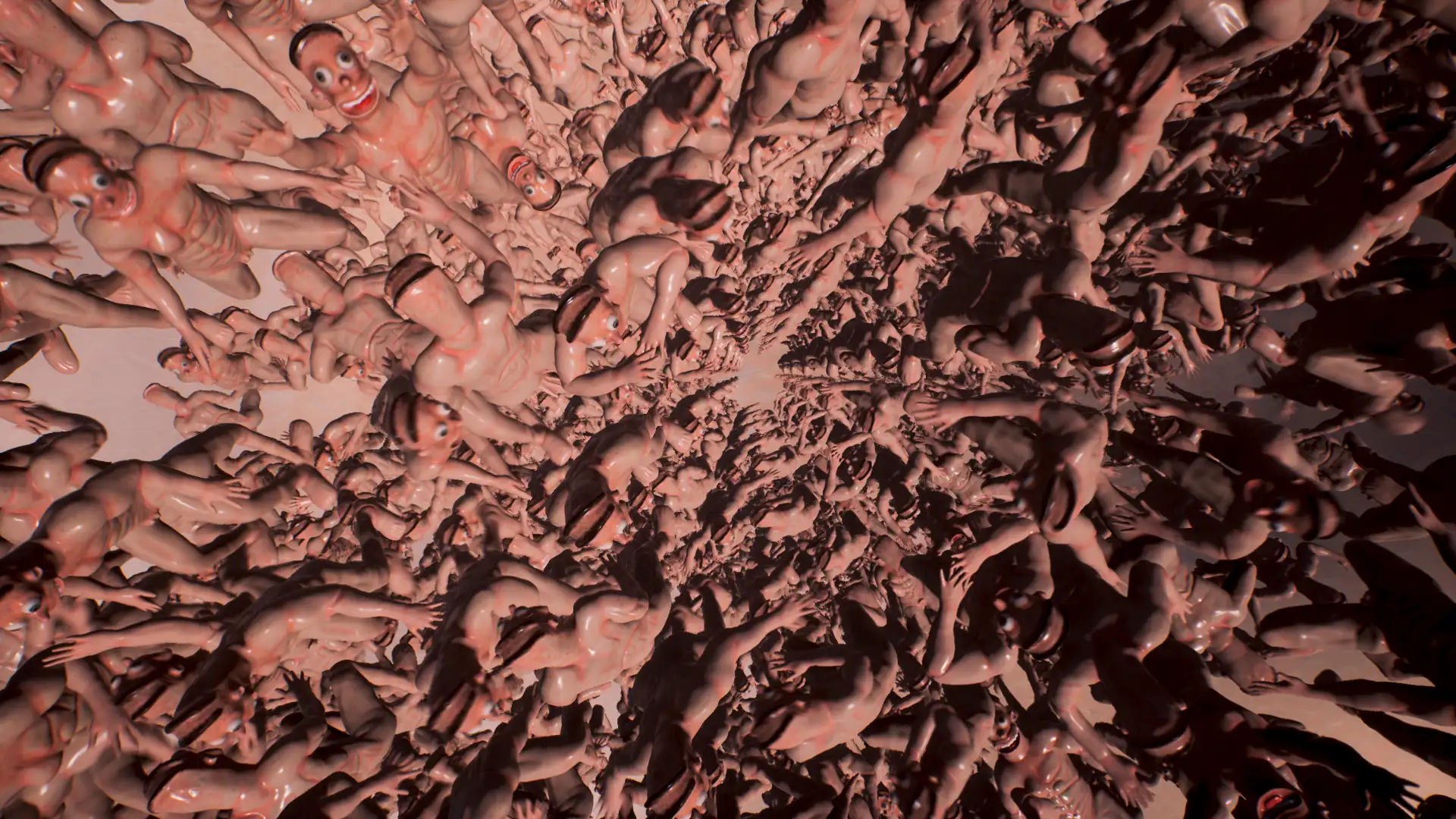

This complexity takes form in the construction of equally labyrinthine environments in which to pit the opposing forces of ‘conservative’ and ‘radical’ politics and aesthetics. The use of objects and Images to explore these issues mimics, even as it questions and critiques. the practices of museum display. Howlett’s quasi-museological environment is one in which truth is always uncertain and open to debate. Howlett presents items ranging from ‘tribal’ artefacts (both ‘authentic’ and ornamental) to live animals and insects. He cajoles us with manipulated footage of sporting kings and emperors, engages us in simulated warfare with sci-fi colonialists. entertains us with categorised and compiled footage from Hollywood war films and educates us with outdated ethnographic texts.

Importantly, the appropriations of prosaic landscape paintings, re-presentation of tribal artefacts and provision of computer games consist of a mixture of ‘authentic originals’, ‘assisted readymades’ and items painted, carved, moulded or generated by Howlett himself. While in some cases the products of these labours are more apparent than in others, it remains unclear whether these are acts of tribute, parody or one-upmanship. These acts of appropriation raise questions of ownership and value. perhaps most clearly demonstrated in the landscape paintings purchased from ‘op shops’.

To these paintings, Howlett has added various figures and slogans, some political and some advertorial. Is the alteration of their content an elevation from the merely decorative to the politically purposeful or is this an act of colonisation in which one artist claims ownership of the work of another? This would certainly seem to be the case when he signs a work on behalf of the original artist – as if their anonymity renders the works authorless and therefore ripe for reclamation. Or is this an act of unrequited collaboration as evidenced by the listing of artist’s names in the gallery alongside Howlett’s own?

Similarly, the use of artefacts would seem to reflect a coloniser’s desire for the fetishes of ‘primitive’ superstition, or at the very least for exotic souvenirs. Yet alongside these artefacts (authentic or otherwise) are objects that Howlett has crafted. As with the landscape paintings. the distinction between the genuine and ingenuous articles is not always clear; some are originals, some have been modified or fabricated from scratch, to varying degrees of plausibility. The more obvious fakes include weapons made using everyday ‘Western’ objects such as cricket bats and fence palings. These objects appear to be the products of some sort of extreme suburban primitivism or the trappings of a very dangerous game.

An equally ominous game is found situated amidst a confusion of monitors and computer games. Here stands an arcade style game and an invitation for the viewer to assume the mantle of Coltan5 the barbarian using a virtual reality helmet modelled on Papua New Guinean mud masks. Donning this mask, we become a player in an environment made up of fragments of the gallery environment itself. Our perception is both focussed and distracted by the mask itself. The mask, like the story behind it, not only frames our view of the world but also adds yet another layer of complexity to the worlds in which we operate.

It seems that one task that Chris Howlett sets for himself is to articulate this complexity; to question the view of the world that is presented to us. Yet perhaps the most pressing question that can be asked by (or of) Chris Howlett is this: how can an artist engage with politics in a meaningful way? When as Brecht suggests art does take on the responsibility of shaping society, how can it do so other than by playing on our ideals and aspirations – and consequently taking on the strategies of advertising and propaganda? In other words. is an artist’s desire to ‘make a difference’ compromised by this very desire, inherent in it the necessity for ‘taking sides’. Is it possible for an artist to engage in politics without taking sides?

It appears that this is the task that Chris Howlett sets for himself – to present his own voice amongst (rather than above) a million others. Rather than a one-sided debate, we are presented with a cacophony of dissent and argument, not simplified or diluted but dispersed around the room. It is up to us to pick through the rubble of Ideologies, to tread the fine line that Chris Howlett draws between seduction and repulsion, and to make up our own minds.

CHRIS HANDRAN IS A BRISBANE BASED ARTIST, WRITER AND CURATOR.

FOOTNOTES

- Chris Howlett, in conversation, October 2004.

- This quote is usually attributed to Bertoldt Brecht. It has also been attributed to figures such as Karl Marx, Vladimir Mayakovsky and Leon Trotsky and appears in varying forms in their writings. One of the more extreme versions suggests: ‘Art is not a mirror held up to reality, but a hammer with which to smash it’.

- Earlier editions were staged at QUT Art Museum and the Farm Space, Brisbane.

- Joseph Goebbels quoted in Eduardo Cadava Words of Light: Theses on the History of Photography (1997) Princeton University Press, New Jersey, p.83.

- Coltan is an abbreviated name for columbite-tantalite, a vital element in the circuitry for cell phones, computer chips, nuclear reactors, computer games and many other electronic devices. Its high market value has served to exacerbate conflict in the Congo, where around 80 percent of the world Coltan supply is found.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.