NEW DAWN: Part II

An Interview with Chris Howlett

MATHIAS JANSSON ... continued ...

MATHIAS JANSSON Art is a statement. Not necessarily with a distinct political agenda but art always reflects on the contemporary. When the Spanish painter Francisco Goya (1746–1828) created the series “The Disasters of War” it was a way to describe and protest against the horror that affected the civilians during the Spanish civil war. Andy Warhol the inventor of Pop Art made paintings and prints that put questions about mass consumption and advertising into focus. Today we can again see a greater awareness for political and social questions among artists. Probably a reaction against the turbulent world we live in with wars, climate threats and financial crises.

The International Occupy Movement against social and economic inequality in the world is also a result of a bigger public awareness about these issues. In Europe both the Berlin Biennial (2013) and the famous Documenta (2012) exhibition in Kassel all accentuated the complicated relationships between political, social and economic issues within their curated artworks. I want to claim that artists are some kind of Superheroes that will save our worlds from catastrophes and injustice. But artists of today have the ability to catch trends in contemporary social space, reflect and visualize these questions in a broader and deeper cultural context to the audience. Artists today often take the roll of an important complement to news and political movement to give us new perspective on contemporary issues.

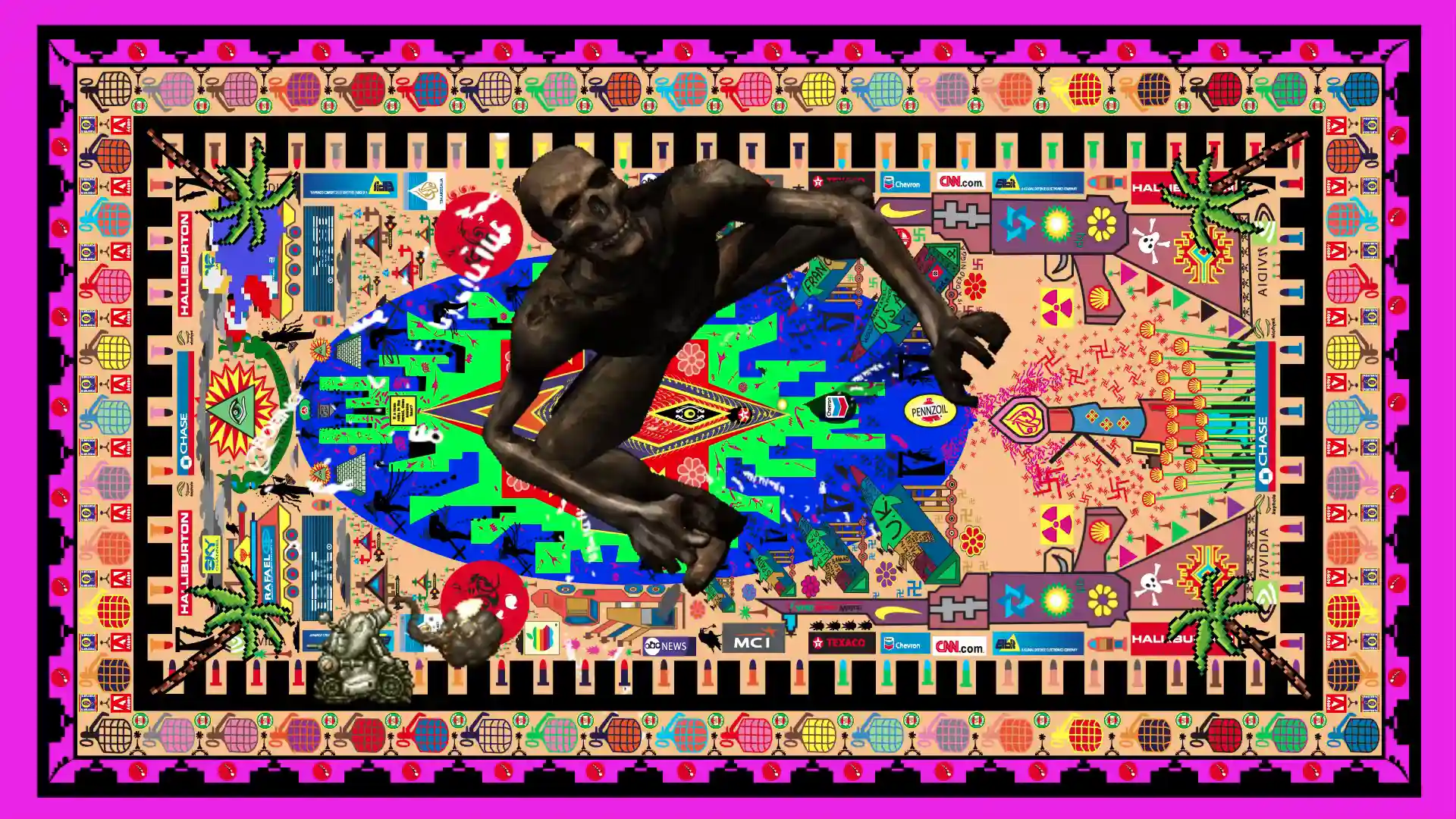

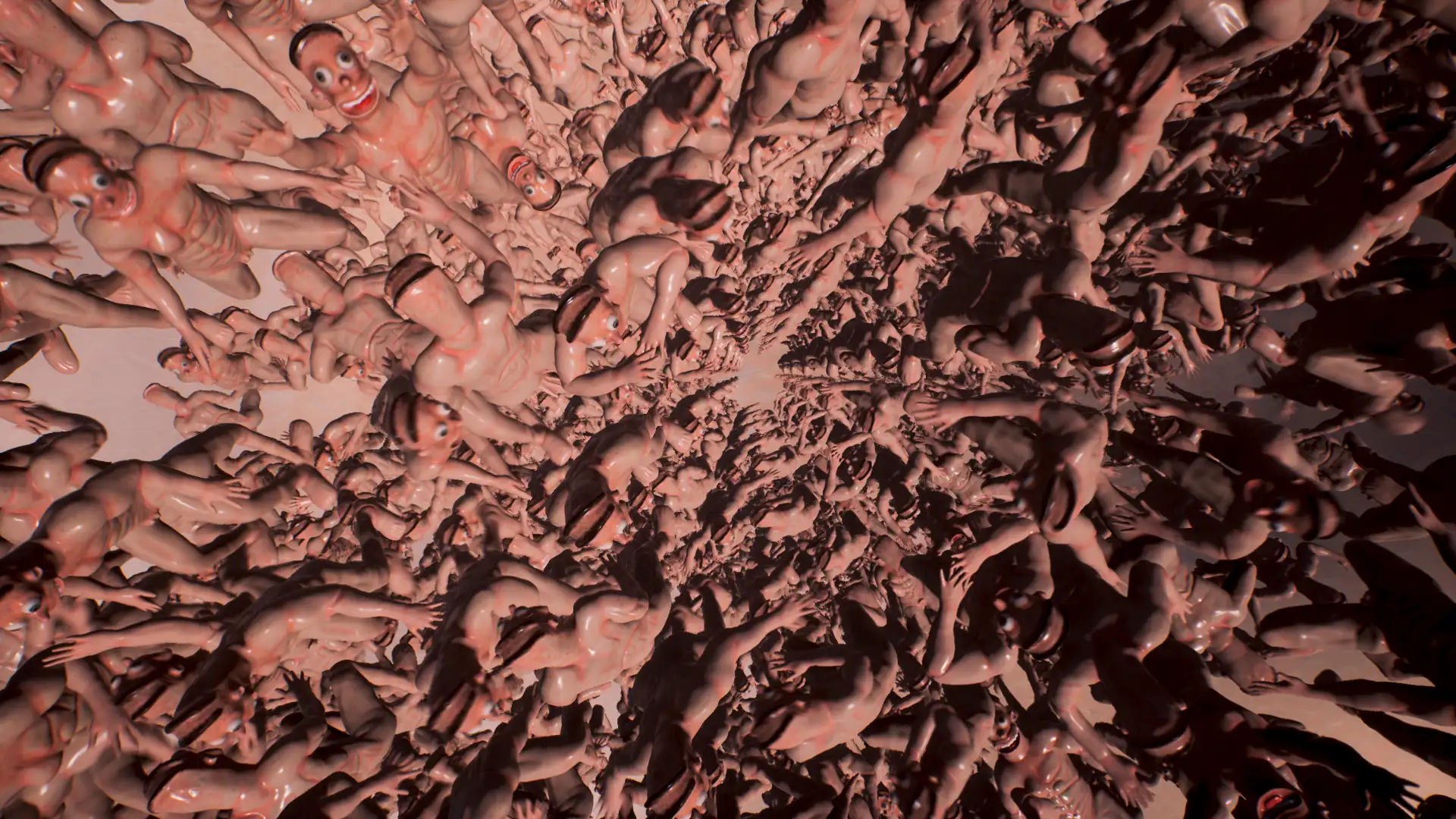

above: New Dawn: Part II, 2013. Installation details. Metro Arts, Brisbane, Australia.

Jansson: Do you see yourself as a political artist?

Howlett: Assuming the role of a political artist and characterizing oneself in this fashion is a very difficult mantle to adopt, sometimes this is what the public, your peers or even the media maps onto you and your Art. On some level, I think it’s quite a personal decision an artist makes to describe themselves in this way. I don’t believe that Art is a form of political activism, because of its deep seated roots in European Aesthetics, Philosophy, and Art History.

In other instances, it’s Art’s refusal to bend to any pre-described function or static role in society that convinces me that it is the only political space left to inhabit – politics just can’t deal with the majority of ideas that artists try and materialize. That is not to say that politics or the Political do not play a role in art making and an artist’s intention for the ideas behind their work, but sometimes we can make too much out of Art or an artist’s work and not enough out of actual events on the ground, that often have nothing to do with Art.

Creating an art work opposing the war in Syria is not going to stop the war in Syria, if that was the intention, but it can create interstices between you and a viewer which can produce a symbolic exchange that can shift a person’s perspective on a contentious point of view. But is that really a political act?

I think there is a tension created out of some kind of relationship between Art and the Social which can give rise to feelings of emancipation or enlightenment. However, Art can also serve the opposite, where it becomes about oppression, manipulation and control. These relationships and contradictory effects are complicated further by artwork labels which assign one artist as Political over another who is not. This becomes redundant, since we’re all trapped within the Social of which the Political is part – we just operate in different circles from one another that intersect at given points.

Everything is Political and nothing is, it’s irrelevant. For me, it comes back to the artist’s intention for their work and how the objects, formalism or ideas create discourse or try to self-consciously resist it. This type of reasoning also raises many paradoxical and contradictory emotions in me since I’m still not sure what Art is for? This is what attracts me to it and the fact that most people don’t really know what it is either.

When I was in graduate school, if Art was not critical it was not Art. This was quite a narrow position to put forward, but at least it was a position I could react against which both frustrated me and gave me license to try and construct meaning around my ambivalent feelings towards the role of the artist and what it means to devote one’s life to this pursuit. I’m still trying to understand these different models of Art and how they’ve given me a space to test out my theories while also allowing me to develop a sense of identity through the knowledge that I and others have developed around my practice.

War is just one phenomenon that interests me within popular culture It’s just as important as love, cheeseburgers or bubble-gum, which are all simply another form of material to use in order to create situations that may make possible new forms of social bonds to develop between my work and those who become a part of it. I don’t think that is too much to ask for.

Jansson: In the exhibition you have been working with both traditional hand-made objects but also used 3D-printed models. In many of your work you are mixing objects from the virtual and the real world, so that the borders between the virtual space and the real room are erased. In the exhibition it looks like the room has been flooded with objects from these two worlds and mixed together. How do you see the issues of copy, (pirate-copy), original, real and virtual object working together?

Howlett: The facsimiles that arise out of my sculptural practice cross over and blend many different forms of realities, each with their own sense of formalism. Some of the objects are cast directly from the real world while others are not and either come directly printed from a virtual space or are sculpted out of my imagination; some have matching in-game textures applied to their surfaces while others are directly using the natural object in the studio as a colour guide. Within the body of works there is also a colour called Natural Grey applied to various objects to represent the early design processes behind the manipulated forms within a 3D world which could also cross over into our real space, yet they are cast from objects tied to the everyday.

The objects’ skins (game terminology for textures applied to objects referred to as “Actors”) are either airbrushed, or their colour is mixed in to them during their liquid state before they cure. Some are dipped directly into paint, while others are hand brushed onto their surfaces. A number of objects either have a highly detailed lacquered and fetishistic surface while others have a slightly out of focus, low-res feel to the way they were airbrushed. This out-of-focus effect is meant to denote how game engines need low-res polygons and texture maps to maintain the real speed and frames per second rates.

Otherwise the gaming experience starts to lag and the reality becomes less immersive and therefore less real. It’s interesting now how speed and time are translated through how much money you’re able or willing to pay out for a fast CPU and graphic card; how fast you’re able to play a game is directly linked to your socio-economic position, age and class. I guess this is just another small example of what Virilio meant by ‘accelerated modernity’; how time and space are gradually shrinking and speeding up on us and what this could mean for our possible futures.