Nicholas Bourriaud has described the existence of a ‘precarious aesthetic’ in contemporary art that exudes the overwhelming heterogeneity of the consumer era. Such art is characterised by,

[S]aturation; the use of “poor” materials; a failure to distinguish between scraps and objects of consumption, between edible and solid; and the rejection of any fixed compositional principle in favour of installations that seem nomadic and indeterminate.1

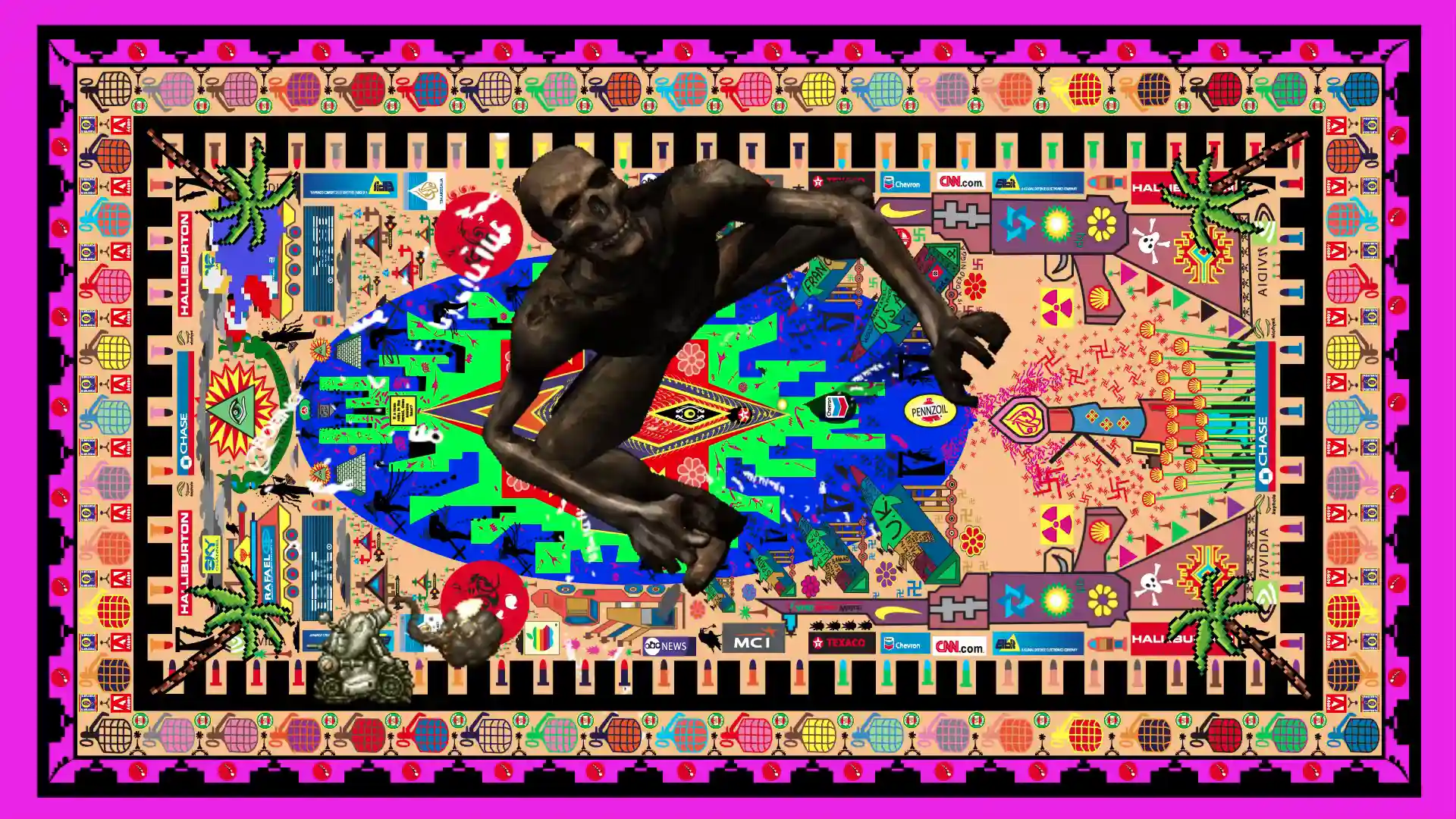

Bourriaud refers to the art of Thomas Hirschhorn and Jason Rhoades in relation to a precarious aesthetic, and the frenetic tone of Howlett’s installation was certainly reminiscent of Hirschhorn’s Caveman, 2003, for it shared an ambitious scope and explicit political content. As in Hirschhorn’s installations, Howlett’s show forced the viewer to confront a veritable cornucopia of everyday detritus – from toilet paper packets to masks, from boxes of apples to children’s clocks, from Australian flags and sports jackets, to coca cola bottles, mock bananas and pineapples. The artist also installed a group of moulded yellow sculptures representing various commodities such as petrol cans, axes, vacuum cleaners, tyres, and lamps, some of which rested in a supermarket trolley. This was supplemented by pin-ups, op shop paintings and prints, magazine covers, and advertising and merchandise posters that were hung on the walls and every other available space.

The show’s title was gleaned from a description of World War II propaganda posters; and so the inference was clear: the media is not just about entertainment, but is also a primary vehicle for the dissemination of consumerist ideology and other propagandistic endeavours. The magazine hoardings that adorned the walls showed dramatic images of Osama Bin Laden and Saddam Hussein, which also illustrated the politics of the media sphere in 2004-5. They were controversial figures during the invasion of Iraq in a war that proved to be quite divisive in many countries. The invasion provoked a raft of protesters who marched on the streets and flouted handmade posters that proclaimed their views. Howlett included a sampling of these DIY posters with hand painted messages such as “People R Dying Stop the War”, “War Fuels War”, and “Be Afraid. Your government depends on it”. The installation thus became the arena for a shouting match between contending forces; indeed, this incredibly cluttered and at times confusing exhibition mimicked the kinds of debate waged in mass media formats. Curator Chris Handran aptly described this scene,

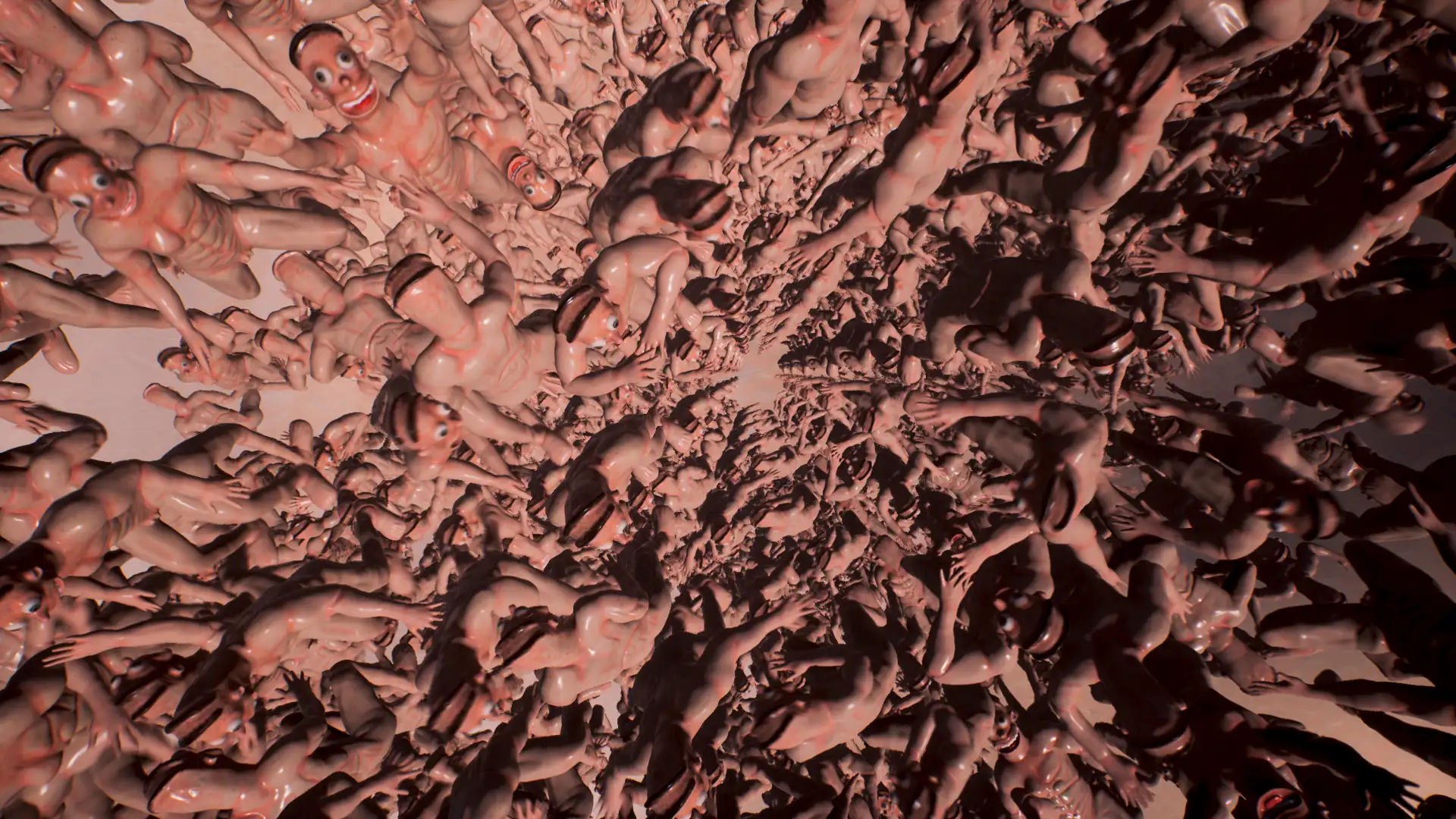

This ambivalent installation therefore offered a mediated menagerie where war and violence became forms of entertainment. Numerous monitors in the centre of the installation displayed footage covering a gamut of spectacles and entertainments, including the 9/11 attacks, American sit-coms, extremist websites, and Sesame Street’s voracious Cookie Monster. There was also a Sony Playstation that ran an interactive game based on toy soldiers, and a Coltan axe-wielding barbarian scenario, which could be played using a helmet modelled on Papuan mud masks. By playing these games the viewer became implicated in the entertainment as war factor. The message of such activities announced an indivisibility between democratic freedoms, the commodity world, entertainments, and the kind of geopolitical sweetheart deals that support repressive dictatorships, weapons’ industries, and other dubious enterprises that keep the whole shebang chugging along.

Howlett’s installation also pondered questions about how to find truth in a world where whoever controls the media image selects the information by which we may know the nature of social reality. This simulational condition also generates an overwhelmed and fearful populace that is prone towards forms of hysteria, and this is of course the psychological tide upon which the masters of the tabloid media have built billion-dollar empires. Howlett’s view of this state of affairs was expressed with some vehemence, but he was also pragmatic as in keeping with the post-avant-garde acknowledgement that artists no longer possess special expertise or superior knowledge, nor do they have much power to influence public debate in the media sphere (unless one produces a diamond encrusted skull perhaps).

clockwise from top: Hire Me Out: Expanded business card, 1999/2000. Acrylic paint on wall. CalArts, California, Los Angeles; Hire Me Out: VHS archive detail (nine VHS tapes), 1999/2000. NTSC, 720 x 576, approx. 10 hours. CalArts, California, Los Angeles

In 2006 Howlett moved to Melbourne where he produced In/Out at the Blindside Artist Run Space. This small installation consisted of video, sound and drawings. It was a sparse, even bare installation, which was in marked contrast to the bustling assault of “Weapons”. However, the scant letters that decorated the walls and the lone corner monitor were accompanied by an aural overload of blaring music that dramatically assailed the senses. This deployment of sound art represented another means by which the artist could extend his preoccupation with the nature of contemporary social reality.

In the aural component of the installation a recording of the artist’s and his sister’s responses to word-association tests provided a tonal code based on the words “in” and “out”, which were turned into a distorted soundtrack. “Weapons” focused on the power of advertising and other forms of propaganda that employ the ‘psychological barrage’ principle to influence people’s thoughts. But, “In/Out” approached the phenomenon from the ‘inside’, as word-association tests are used to expose the inner workings of consciousness. This relies on probing, mining and influencing the operations of interior life. In order to unearth this material from his and his sister’s mind Howlett established a set of procedures to record their answers:

Step 1. Record all responses using a handheld mobile phone.

Step 2. Respond to the word with the first thing that comes into your mind.

Step 3. Respond to your responses using the word “IN” to describe them tonally.

Step 4. Respond to your responses using the word “OUT” to describe them tonally.

Some of his sister’s responses were as follows: Black = Blue; Death = Aphid; Holes = Divot; Kind = Pink; Ticking = Bomb. The word-association tests were also illustrated in a video. As noted, the recording of this process was slowed down and distorted and was used to accompany fragmented pictures of Howlett’s body parts, which spun at various speeds on the screen announcing psychological and physical states of fragmentation.