HOWLETT’S INSTALLATION ALSO PONDERED QUESTIONS ABOUT HOW TO FIND TRUTH IN A WORLD WHERE WHOEVER CONTROLS THE MEDIA IMAGE SELECTS THE INFORMATION BY WHICH WE MAY KNOW THE NATURE OF SOCIAL REALITY.

This work suggested that although we are the focus of psychological tests and other intrusive forms of measurement – that are in turn transcribed into various communicative forms to represent and control us – there are aspects of human experience that are unaccountable and stubbornly refuse such managerial dictates.

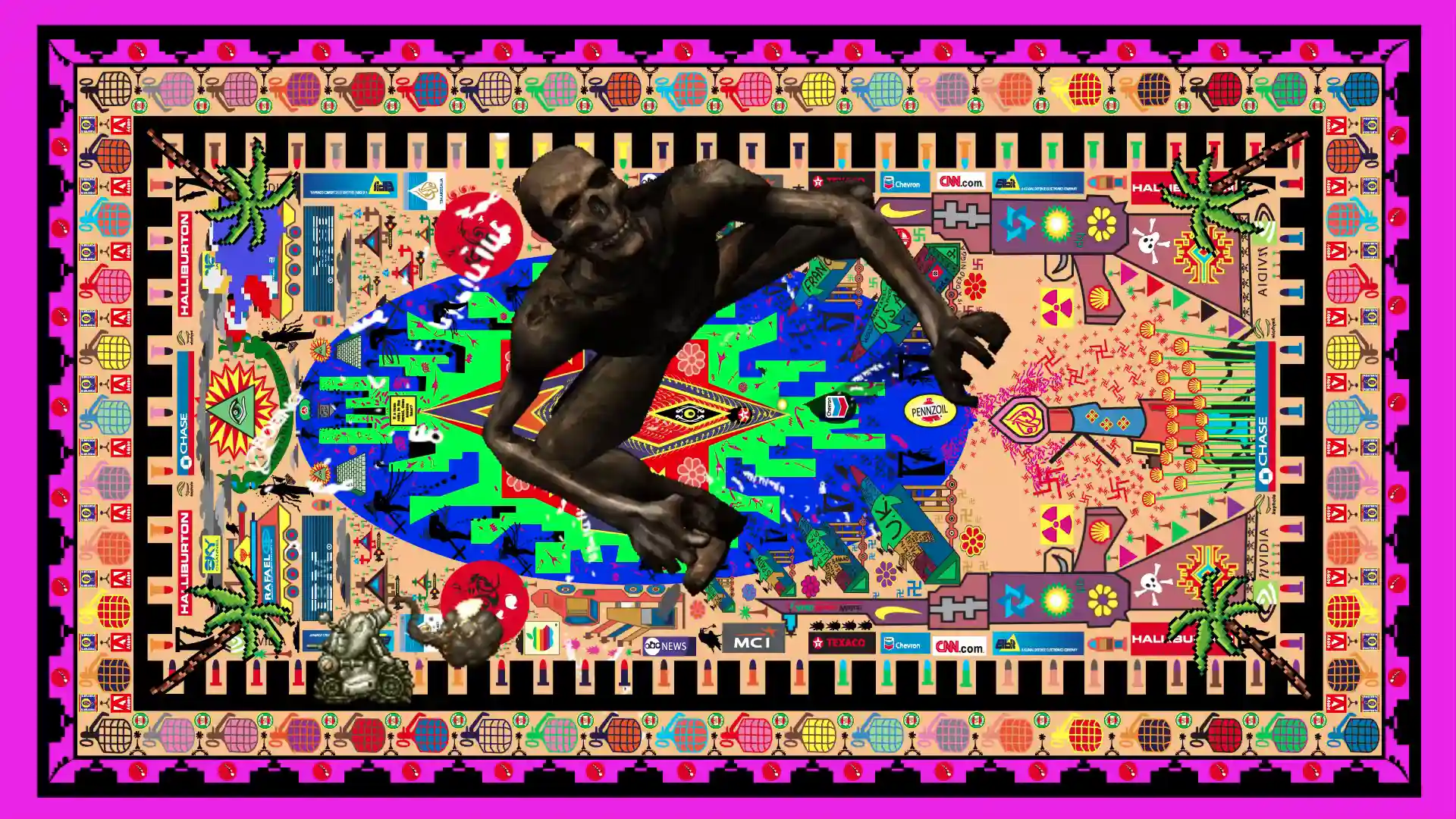

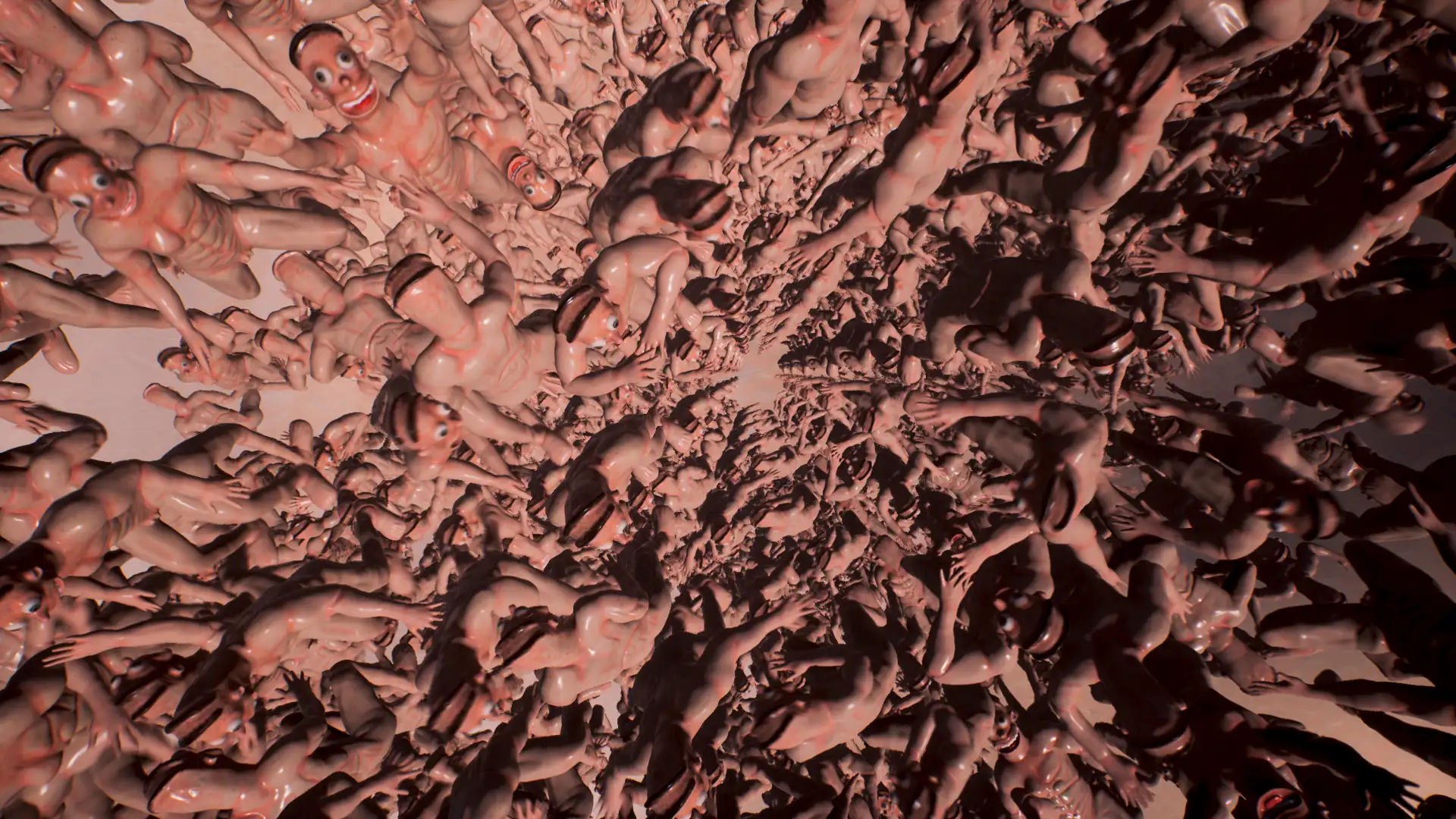

from top: Bushstalkers. 2009. Machinima video still. PAL, HDTV, 1920 x 1080, 16:9; Bushstalkers, 2009. Installation detail.

Metro Arts, Brisbane. Photography Brock Yates.

On his return to Brisbane in 2008 Howlett produced Christopher Howlett Enterprise: this is not art but design. This was an on-line work that covered multiple areas including extending his interest in digital media, exploring aspects of Relational Aesthetics, and returning to his conceptual roots. The idea for this project emerged in 2006 when he received government assistance to open an interactive design studio called Post Studio Arts.com (this is a plug). As any self respecting artist will know, work is something one does to earn money to do art, but Howlett saw other points of convergence between his art and business, as he was in effect producing graphic design ‘art work’ for clients while building a company brand.

This project drew attention to some of the more intractable dilemmas facing the post-avant-garde as it sorts through older artistic legacies. One perennial conflict involves the avant-garde’s relationship to mass culture. Once, the artist could claim autonomy from consumer capitalism, but today’s artists have mostly accepted that this distance has all but evaporated. In keeping with this attitude Howlett does not delude himself into thinking that his business offers a critical challenge to the status quo, but he does resort to an almost nostalgic deployment of the rhetorical, didactic and bombastic approach of some 60s conceptualists to address the residue of the art/business divide.

One facet of this concern involves confronting distinctions between art and design. In modernism, art was considered to be superior to design. In this schema the latter was a derivative affair that was sullied by its direct engagement with the marketplace. In contrast, artists could have their cake and eat it to, being both ‘above’ the market while selling work here and there. Such views seem anachronistic today, as there are no longer any easy distinctions between art and design, art and business, or art and entertainment. Howlett’s response to this condition was articulated in the following equation:

This problematic sum evokes the style of avant-garde manifestoes; especially conceptual art’s treatment of language in Joseph Kosuth’s formula “Art as Idea as Idea”. It also touches on George Maciunas’ statements about art in the Fluxus manifesto. In Maciunas’ anarchic attack on art’s value system he made the ‘relativity’ claim in which an antidote to the artist’s ‘professional, parasitic and elite status in society’ could be demonstrated by the belief ‘that anything can be art and anyone can do it’. Whereas Fluxus might have been accused of sly connoisseurship or an ersatz artistic revolution Howlett, as always, is much more direct.

He dispenses with subtlety by offering rather simple equations that contain both an assertion and a question. The question reveals much about the artist’s thinking about this topic, for his essential inquiry is: in the normal scheme of things art is not design and design is not art, but if you put the two together somehow it becomes art. Why? The bluntness of such a inquiry makes it pointless to indulge in forms of sophistry that explain how these two can be compatible and incompatible at the same time, especially in an era of cultural industries. Instead, the artist sincerely asks us to share in a logical dilemma and thus establishes an empathy with the viewer that in some respects makes a greater impact than a work like Weapons on the Wall.

Despite the artist’s claims, his approach to Christopher Howlett Enterprise does not entirely conform to the ‘social relations as art’ mantra promulgated by Nicholas Bourriaud and his ilk. However, Howlett does recognise relational art’s insecure place as an ‘interstice’, and this has a direct bearing on his art/design/business nexus. Bourriaud argued that the art world is implicated in a larger economic system, but that it operates in a ‘social interstice’ (a Marxist term referring to a trading community that can elude the capitalist economic context) and so is somewhat insulated from economic ‘corruption’. This is enabled because relational aesthetics artists made art predicated on social relations rather than objects/commodities. Many of these relational-type projects include methods of production that are articulated through invitations, casting sessions, meetings, user-friendly areas, and appointments. These ‘corporate’ methods make claims about ‘insulation’ rather dubious, but according to Bourriaud they still lie beyond charges of capitalist collusion because they offer an ‘operative realism’ that uses mimicry as a subversive strategy that reveals the actual nature of capitalist experience.

Howlett’s design company produces good and services like other design studios, but he wrestles with the task of ascertaining how much his approach actually can exist in an interstice. Does his art offer succour to those who wish to maintain a critical attitude in a neo-liberal era, or is it just another business? Does his art/design nexus offer flexible resistance to the current order, or does it ‘surrender to engineered consent and the pacifying distractions of enforced leisure’? (Hal Foster, “Arty Party” London Review of Books, December 4, 2003, p. 21) One can see that Howlett fears his art might not disrupt consumerist forces as much as materialise and reinforce them, but this admission reveals an honesty that lies at the core of the artist’s practice, and in these confusing times he maintains a kind of integrity. In an age dominated by cynical reason this is no mean feat.

In Flashbacks (2009) Howlett continued to examine the way in which meaning is derived from a multiplicity of places, spaces, mediations and texts. This two-part installation was first exhibited at Brisbane City Town Hall and then later at !Metro Arts Brisbane. It comprised a series of screen based and machinima works including The Long Con with his video footage of an anti-war rally held in central Brisbane, a modified videogame Bushstalker, and a series of ‘modded’ Sims works Michael Jackson 4 ways: Parts 1,2,3 and 4, and Homesteads. This was accompanied by an extensive sound installation of hardware hacked iPod transmitters titled Frequencies. In these installations Howlett presented the viewer with contesting voices about highly politicised issues like the Iraq war and its bloody aftermath, the life and death of Michael Jackson, debates around art and censorship, and the confessional discourse of celebrity talk shows. These topics were used to encourage the viewer to consider the complications of comprehending what is real in the enunciative field and how these are related to the ideological compulsion to render truths from moral perspectives.